A series of atmospheric rivers drenched western Washington this December, delivering more than five trillion gallons of rain in a single week, triggering widespread flooding, infrastructure damage, and hundreds of emergency rescues. While atmospheric rivers are a familiar winter feature in the Pacific Northwest, climate change is amplifying their destructive potential by intensifying rainfall, raising winter temperatures, and increasing the likelihood of rain-on-snow events that overwhelm rivers and flood defenses. This event offers a clear window into how flood risk in the region is evolving.

Atmospheric Rivers in the Sky, Floodwaters on the Ground

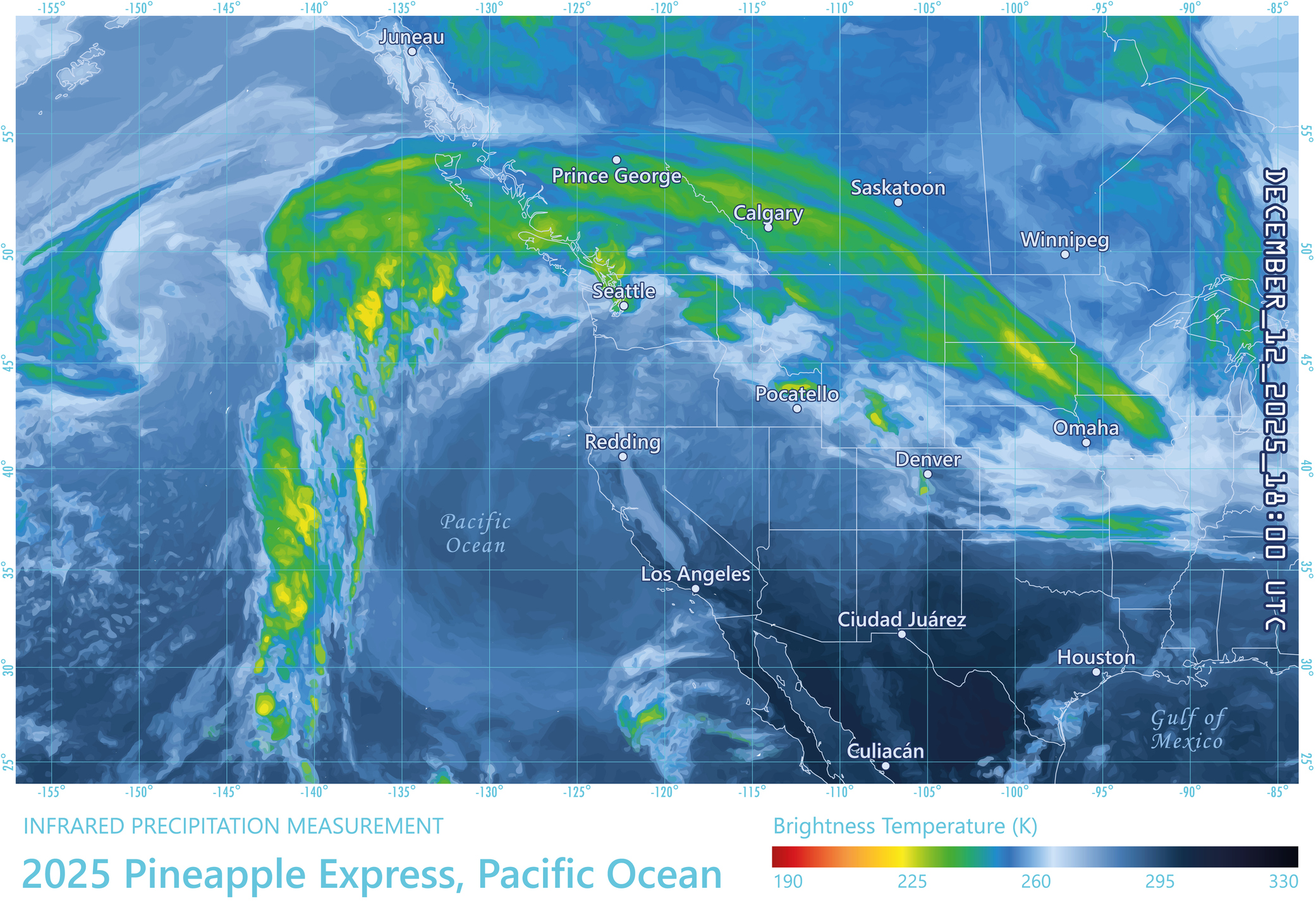

From December 7–14, a powerful sequence of atmospheric rivers stalled over western Washington, funneling vast amounts of warm, moisture-rich air into the region. Atmospheric rivers – long, narrow corridors of water vapor – are responsible for 30–50% of annual precipitation along the West Coast and can transport more water vapor than the Amazon River carries as liquid flow. While these systems are a critical component of the region’s hydrological cycle and can help relieve drought, they are also the dominant driver of flood damages in the western United States.

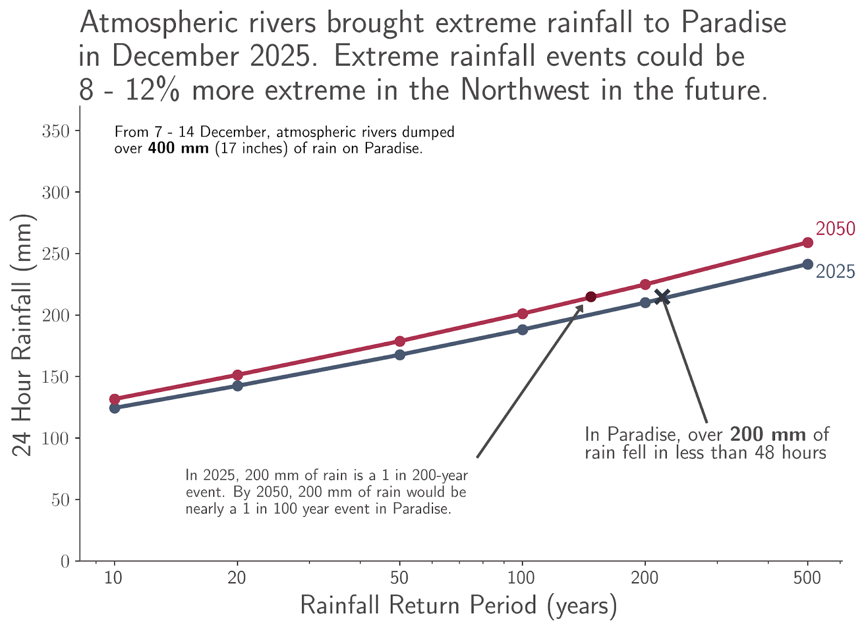

During this event, more than five trillion gallons of rain fell across western Washington in just one week. Because atmospheric rivers are not only wet but also relatively warm, much of this precipitation fell as rain rather than snow, even at elevations that typically accumulate early-season snowpack. At locations such as Paradise on Mount Rainier, rainfall totals were consistent with near–200-year events, while much of western Washington experienced rainfall consistent with 100-year return periods.

As rain fell onto snow that had accumulated earlier in the season, rapid snowmelt compounded runoff. This combination of heavy rainfall and accelerated meltwater led to widespread river swelling across the region.

By mid-December, over 75% of Washington rivers were recording 7-day average streamflows at or above 90% of their historical maxima, according to U.S. Geological Survey gauges. Rivers including the White, Green, Nooksack, and Skagit exceeded flood stage, triggering thousands of evacuations. Along the Skagit River floodplain, nearly 100,000 people were at risk as water levels approached — and in some locations, exceeded — historical records set in 1990.

Flooding impacted major transportation corridors, including the closure of more than 50 miles of U.S. Highway 2, repeated closures of Interstate 90, and downed power infrastructure along Interstate 5. More than 100 people were rescued from floodwaters during the event, and at least one fatality was reported. State officials immediately committed $3.5 million to emergency response, with total damages expected to rise as impacts continue to be assessed.

Why Warmer Skies Make Atmospheric Rivers More Dangerous

The Pacific Northwest has always experienced atmospheric rivers. What’s changing is how much rain they carry, how warm they are, and what happens when they arrive.

Extreme Rainfall Is Becoming More Extreme

A warming atmosphere can hold more water vapor, increasing the potential intensity of extreme precipitation events. Along the West Coast, atmospheric rivers dominate these extremes. Scientific analyses show that while average precipitation may not increase dramatically, the most intense rainfall events are becoming more intense, while lighter rainfall events may decrease.

Event-based attribution studies already suggest that climate change is amplifying atmospheric river rainfall. For example, analysis of a major 2017 atmospheric river event found that climate change increased rainfall totals by approximately 11–15%. By late in the 21st century, extreme moisture days associated with atmospheric rivers could become nearly 300% more likely than under historical conditions.

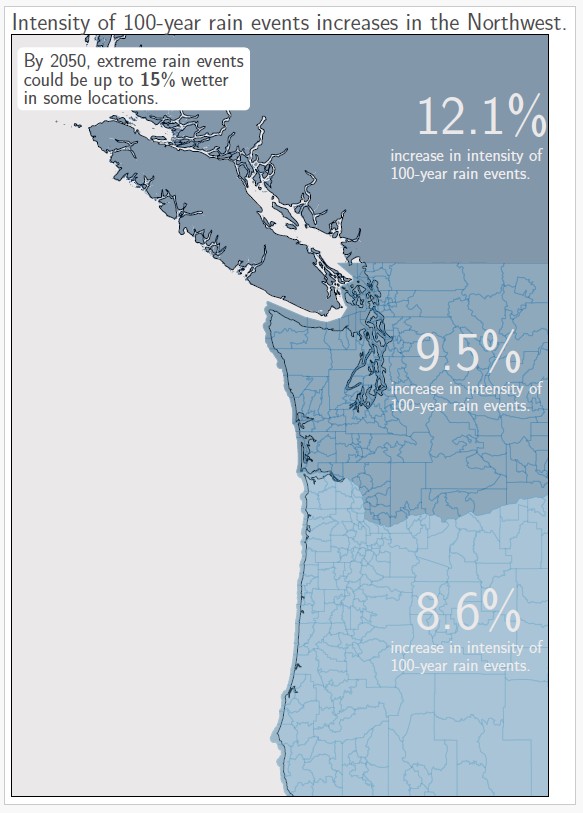

Consistent with this broader body of research, Jupiter’s ClimateScore Global projects increases of 8–12% in extreme rainfall events across western Oregon, Washington, and southwestern British Columbia over the next 25 years, with localized increases reaching up to 15%.

In this context, rainfall totals observed during this December event – already reaching 100- to 200-year return periods under historical baselines – are projected to become nearly twice as likely by mid-century, underscoring how the tail of the precipitation distribution is shifting.

Rain-Driven Flooding Is Intensifying

Atmospheric rivers are responsible for approximately 80% of flood damages in the Pacific Northwest, and flood losses increase exponentially with the intensity and duration of these events. The most extreme atmospheric rivers routinely generate tens to hundreds of millions of dollars in damages, with the largest events exceeding the billion-dollar disaster threshold.

Climate warming is expected to further increase flood risk by altering the balance of atmospheric river types. Studies indicate that warming increases the number of atmospheric rivers that challenge water-management systems by 1–3 additional events per year, while reducing the frequency of “primarily beneficial” drought-relieving events and increasing the number of “primarily hazardous” flood-driving events.

Atmospheric rivers contribute to both:

- Pluvial flooding, when intense rainfall overwhelms surface drainage, and

- Fluvial flooding, when rivers exceed channel capacity due to runoff and snowmelt.

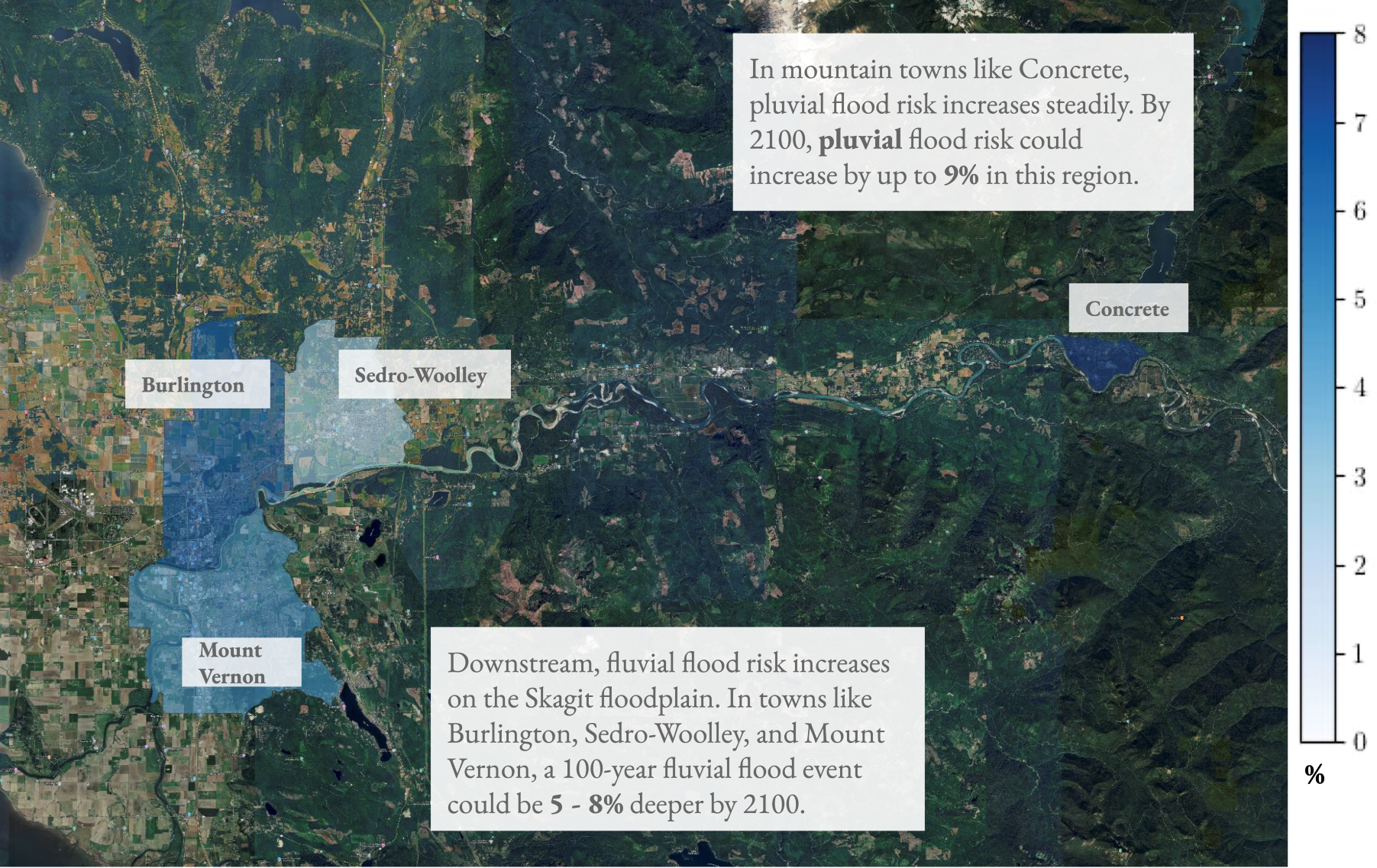

In mountainous regions of Washington’s Cascade Range, pluvial flood risk for a 100-year event is projected to increase by 3–5% by 2050, with increases of up to 9% by 2100 in some higher-elevation communities. Downstream along major river floodplains such as the Skagit Valley, projected changes in fluvial flood depths are more modest in the near term, but by late century 100-year fluvial flood depths increase by approximately 5–8%.

Importantly, these increases occur even where population density is relatively low, particularly in communities with expanding development along floodplains – amplifying exposure as hazard intensifies.

Warmer Winters Create A Hidden Multiplier: Rain On Snow

Temperature is a critical and often underappreciated amplifier of atmospheric river flood risk.

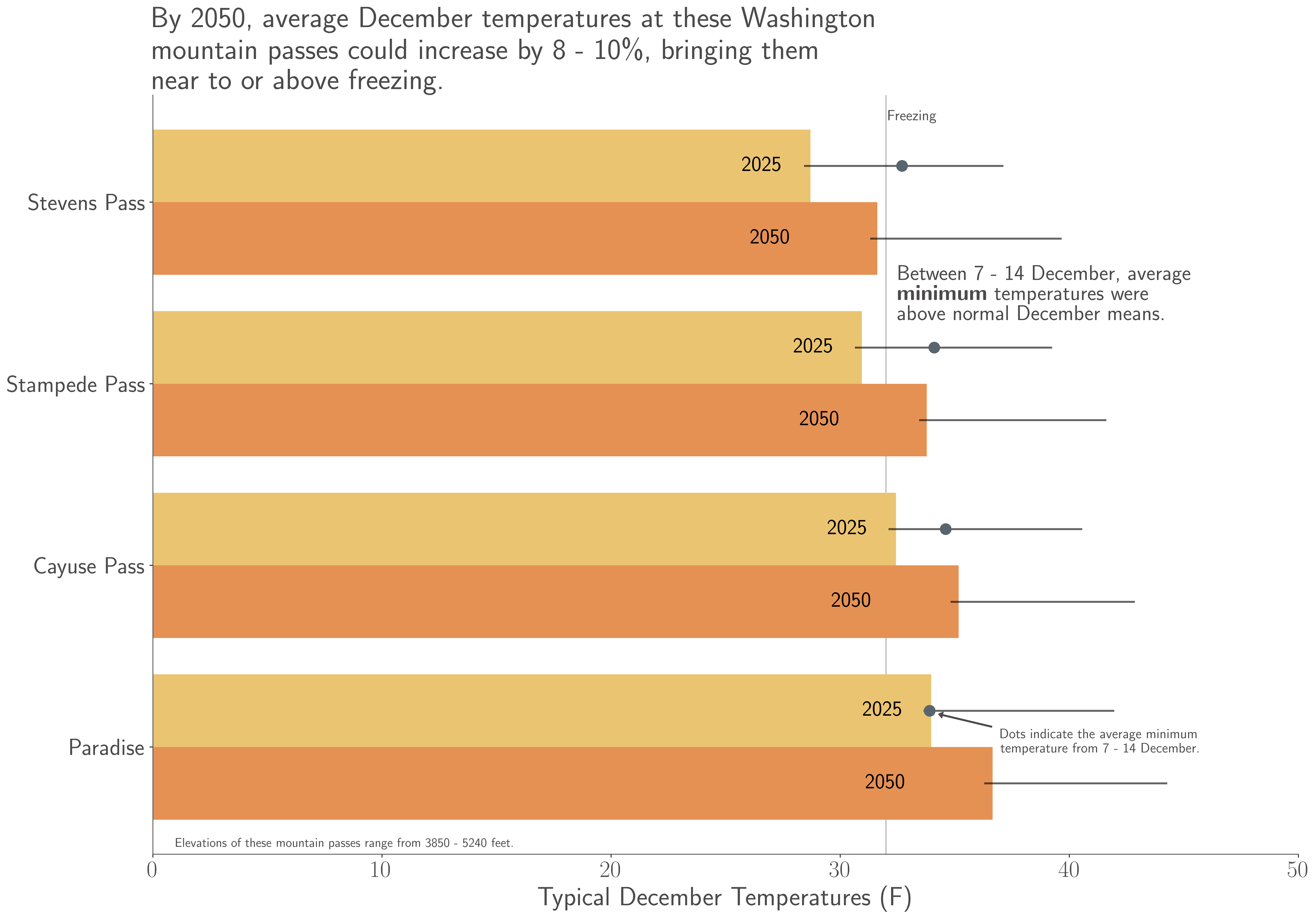

Atmospheric rivers tend to bring warmer-than-average winter temperatures. During this December event, overnight low temperatures at multiple Washington mountain passes remained at or above freezing for more than a week, conditions highly conducive to rain-on-snow flooding.

When rain falls onto an existing snowpack, the melt accelerates, the soil saturates, and runoff surges downstream. This mechanism significantly increases downstream flood risk, particularly in basins draining the Cascades.

Climate projections indicate that average December temperatures at Washington mountain passes could warm by 8–10% within the next 25 years, further increasing the likelihood that precipitation during atmospheric river events falls as rain rather than snow. Over longer timescales, snowlines during atmospheric river storms could rise by as much as 700 meters by late century, sharply reducing snow accumulation at mid-elevations and altering the seasonal timing of runoff.

The Bigger Picture: Flood Risk Is Compounding

Atmospheric rivers don’t act in isolation. Their impacts compound with other climate-driven stresses:

- Infrastructure designed for historical conditions remains fixed, even as rivers carry more water. As streamflows increase in a warmer climate, levees remain at the same level. And saturated levees are more vulnerable to failure after repeated storms.

- Post-wildfire landscapes are especially prone to landslides and flash flooding. Burn scars from recent wildfires such as the Bolt Creek Fire, are especially vulnerable to flash flooding and landslides during intense winter storms.

More broadly, research indicates that every additional 1°C of warming from present conditions increases average annual flood damages in the western United States by roughly $1 billion, with even a 0.5°C increase associated with hundreds of millions of dollars in additional annual losses.

Since the mid-20th century, every county in Washington has experienced at least one federally declared flood disaster, and the frequency of such events is expected to continue rising as precipitation extremes intensify.

A Narrow Escape – And a Warning

During this event, forecasts from the Northwest River Forecast Center and National Weather Service accurately anticipated extreme river levels, enabling the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to enact flood-control measures that likely prevented catastrophic losses along the Skagit River. Emergency floodwalls in Mount Vernon held, averting what could have been a record-setting disaster.

But this outcome should be viewed as a warning rather than reassurance.

Forward-Looking Analytics Are Table Stakes

Atmospheric rivers are already among the costliest climate hazards in the Pacific Northwest, and continued warming is expected to make them more intense, more damaging, and more likely to overwhelm infrastructure designed for historical conditions.

For risk managers, infrastructure owners, insurers, lenders, and public agencies, this event provides a clear signal: the magnitude and the compound nature of the flooding align closely with forward-looking risk that is captured in climate-informed analytics – not in catastrophe models.

And that distinction matters.

Decisions about capital allocation, infrastructure design standards, insurance pricing, and resilience planning increasingly depend not on historical averages, but on the frequency and severity of tail-risk events.

Warmer air, heavier rainfall, and diminished snow storage are reshaping flood risk across the Pacific Northwest – turning rare events into expected events.

As atmospheric rivers grow more intense and winter temperatures continue to warm, the financial and operational consequences of underestimating extreme flood risk become more pronounced and materially consequential.

The question is no longer whether these events will happen again; but whether communities, infrastructure, and risk models are prepared for just how much worse they may become.

____________________________

References

- U.S. Department of Agriculture. “Atmospheric Rivers in the Northwest”. Northwest Climate Hub. Accessed 16 December 2025.

- Corringham, T.W., J. McCarthy, T. Shulgina, A. Gershunov, D.R. Cayan, and F. Martin Ralph (2022): Climate change contributions to future atmospheric river flood damages in the western United States. Nature Scientific Reports, 12, 13474. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-15474-2.

- Corringham, T.W., F. Martin Ralph, A. Gershunov, D.R. Cayan, and C.A. Talbot (2019): Atmospheric rivers drive flood damages in the western United States. Science Advances, 5, 13474. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aax4631.

- Zhou, A., 11 December 2025: “How Western Washington’s ‘100-year’ floods are changing”. Seattle Times. Accessed 15 December 2025.

- United States Geological Survey, 17 December 2025. “7-day average streamflow compared to historical (Washington)”. USGS WaterWatch. Accessed 18 December 2025.

- United States Geological Survey, 18 December 2025. “Monitoring location Skagit River Near Mount Vernon, WA”. Water Data for the Nation. Accessed 18 December 2025.

- Warner, M.D., C.F. Mass, and E.P. Salathé, Jr., (2015): Changes in Winter Atmospheric Rivers along the North American West Coast in CMIP5 Climate Models. J. Hydrometeorology, 16, 118-128. doi:10.1175/JHM-D-14-0080.1.

- Rhoades, A.M., M.D. Risser, D.A. Stone, M.F. Wehner, and A.D. Jones (2021): Implications of warming on western United States landfalling atmospheric rivers and their flood damages. Weather and Climate Extremes, 32, doi:10.1016/j.wace.2021.100326.

- Lee, S.Y., Hamlet, A.F., and Grossman, E. 2016. Impacts of Climate Change on Regulated Streamflow, Flood Control, Hydropower Production, and Sediment Discharge in the Skagit River Basin. Northwest Science 90, 23-43. https://doi.org/10.3955/046.090.0104.

- Shulgina, T., and coauthors (2023): Observed and projected changes in snow accumulation and snowline in California’s snowy mountains. Climate Dynamics, 61, 4809-4824. doi:10.1007/s00382-023-06776-w.

- Swanson, C., 17 December 2025. “An emerging threat as WA flooding continues: saturated levees”. Seattle Times. Accessed 17 December 2025.

- Cordeira, J.M., J. Stock, M.D. Dettinger, A.M. Young, J.F. Kalansky, and F.M. Ralph (2019): A 142-Year Climatology of Northern California Landslides and Atmospheric Rivers. Bull. Amer. Meteorol. Soc., 100, 1499-1509. doi:10.1175/BAMS-D-18-0158.1.

- Tuoma, D., S. Stevenson, D.L. Swain, D. Singh, D.A. Kalashnikov, and X. Huang (2022): Climate change increases risk of extreme rainfall following wildfire in the western United States. Science Advances, 8, doi:10.1126/sciadv.abm0320.

- Swanson, C., and B. Kiley, 12 December 2025. “Mount Vernon floodwall holding as crest of flood passes”. Seattle Times. Accessed 15 December 2025.

- Ryan, J., 15 December 2025. “Army takeover of Skagit dams lowers flood waters”. KUOW Seattle, National Public Radio.

- Payne, A.E., and coauthors (2020): Responses and impacts of atmospheric rivers to climate change. Nature Reviews: Earth and Environment, 1, 143-157. doi:10.1038/s43017-020-0030-5.

- Gershunov, A., and coauthors (2019): Precipitation regime change in Western North America: The role of Atmospheric Rivers. Nature Scientific Reports, 9, 9944. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-46169-w.

- Huang, X., D.L. Swain, and A.D. Hall (2020): Future precipitation increase from very high resolution ensemble downscaling of extreme atmospheric river storms in California. Science Adv., 6 (29). doi:10.1126/sciadv.aba1323.

- Higgins, T.B., Subramanian, A.C., Watson, P.A.G., and S. Sparrow (2025): Changes to Atmospheric River Related Extremes Over the United States West Coast Under Anthropogenic Warming. Geophys. Res. Lett., 52, e2024GL112237. doi:10.1029/2024GL112237.

- Deshais, N., 17 December 2025. “WA flooding devastates major roads. What’s the path ahead?”. Seattle Times. Accessed 18 December 2025.

- Cornwell, P., K. Uyehara, A. Zhou, C. Gaitán, and C. Freeman, 9 December 2025. “Major floods sweep Western WA; Skagit River set to shatter record”. Seattle Times. Accessed 15 December 2025.

.webp)