Unprecedented Power, Unfinished Story

Hurricane Melissa made landfall in Jamaica as a Category 5 storm – the strongest to hit the island since records began in 1851. The storm’s central pressure ranked among the six lowest ever recorded in the Atlantic. Winds exceeding 160 mph tore through southern and western Jamaica, where parishes such as Manchester and St. Elizabeth suffered catastrophic flooding and wind damage.

Before landfall, nearly 250,000 people were already without power; by the next morning, three-quarters of the island was dark. Agriculture in St. Elizabeth, one of Jamaica’s key food-producing regions, has been devastated, and Mandeville, the capital of Manchester Parish, sustained heavy structural losses.

After crossing Jamaica, Melissa made a second landfall in southeastern Cuba as a Category 3, then swept through the Bahamas as a Category 2. It is expected to make a final landfall in Bermuda as a Category 1 or 2 storm before turning northeast into the Atlantic. And although Melissa did not make landfall in Haiti, its rains brought catastrophic flooding to the southern part of the country, where at least 30 deaths have already been reported.

The Science Beneath the Surge

The Caribbean Sea was roughly 1.4 °C (2.5 °F) warmer than average when Melissa formed – an ocean anomaly 500–900 times more likely because of climate change. These record-high sea-surface temperatures supercharged Melissa’s rapid intensification, echoing a pattern seen in recent high-end storms such as Maria (2017), Helene (2024), and Milton (2024).

Studies show climate change has made Atlantic hurricanes roughly 8 m/s (18 mph) faster on average over the past five years and increased the rate of extreme rainfall worldwide,. As warmer air holds more moisture, each degree of ocean warming drives heavier precipitation. In tropical cyclones, that translates to 20–60 percent more rainfall than storms of similar strength just a generation ago.

These are not future projections. They are measurable changes happening now.

The Shrinking Window to Rebuild

Only a year ago, Hurricane Beryl inflicted $995 million in damage across Jamaica and caused a 1 percent drop in GDP. Thousands of homes and public facilities were still under repair when Melissa struck. Now, three-quarters of the island is without power, entire parishes are waterlogged, and crop losses will almost certainly deepen food insecurity in the months ahead.

As severe weather events accelerate in both frequency and intensity, each one amplifies the downstream impacts of the last, stretching already limited recovery timelines even further.

- Red tide outbreaks – harmful algal blooms often triggered after hurricanes – could contaminate drinking water and fisheries around Jamaica and Haiti. Such outbreaks can persist for months, complicating both recovery and public health.

- The agricultural damage in St. Elizabeth, one of Jamaica’s main food-producing regions, will likely ripple through supply chains and rural livelihoods, possibly forcing the government to divert scarce resources from rebuilding to food imports and emergency assistance.

- Meanwhile, mass evacuations across Cuba and the Bahamas – nearly half a million people in Cuba and 1,500 in the Bahamas – underscore the regional scale of disruption. Even for countries spared a direct hit, these evacuations typically result in displaced labor forces, strained logistics, and delays in the return of essential services.

Taken together, these compounding crises lengthen recovery time far beyond the initial cleanup. As storms intensify and strike in quicker succession, the Caribbean’s ability to rebuild before the next season grows ever more constrained. For many communities – especially those already struggling with limited resources – each new disaster compounds the last.

And if recovery planning continues to rely on data rooted in the past rather than forward-looking climate projections, some areas could face a nightmarish cycle of rebuilding in place; a near-constant state of recovery that never quite catches up to a dynamically changing climate.

Quantifying a Wetter Future

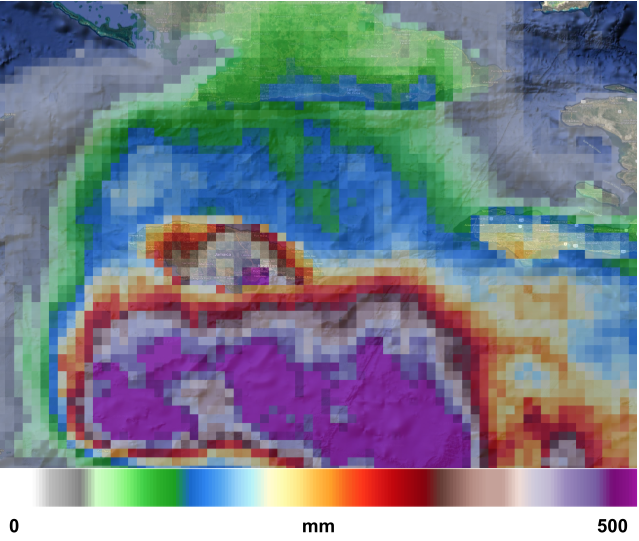

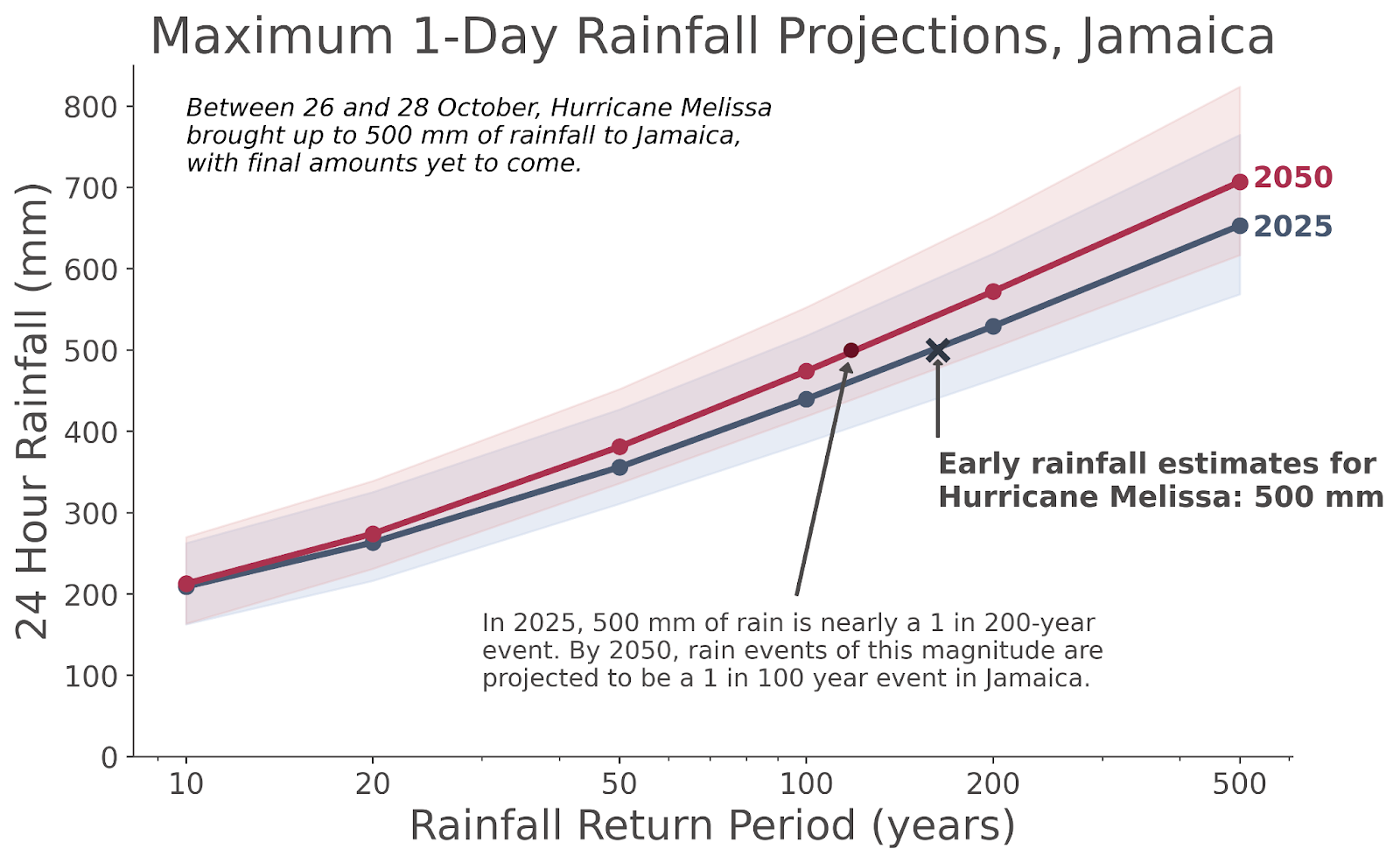

Jupiter’s projections indicate that Jamaica’s 1-day extreme rainfall could increase another 4–8 percent by mid-century, especially in southern and southwestern regions, where Melissa’s heaviest rain fell. A 20-inch storm today could bring 1–2 inches more in the 2050s, transforming what was once a 500-year event into something far less rare.

These insights underscore why decision-makers must plan using forward-looking, physics-based analytics rather than historical records alone. Traditional flood maps, built on backward-looking averages, cannot capture the accelerating pace of climate-driven change.

When the Past No Longer Applies

The climate is changing faster than the records we’ve relied on to understand it. Hurricane Melissa’s rainfall – up to 30 inches across parts of Jamaica, a 200- to 500-year event in Jupiter’s data – makes that point clear. Traditional flood maps and catastrophe models are calibrated on decades of past observations, assuming that the frequency and intensity of hazards will remain relatively stable over time.

But climate change has broken that assumption.

The physical drivers of risk: temperature, precipitation, sea level, and storm dynamics, are shifting faster than historical datasets can capture. “Backward only” models can tell us what was likely, not what will be.

Forward-looking models use climate projections to support quantifying emerging risks under future conditions, not yesterday’s climate. That difference is critical for infrastructure planning, financial stress testing, and resilience strategies that hold up in the world we’re actually facing, not the one we’ve left behind.

Jupiter’s ClimateScore Global integrates the physics of a warming climate to project how extreme weather is evolving. Banks, investors, insurers and governments use these analytics to anticipate future flood and wind risk, quantify exposure, and plan adaptation investments before the next disaster strikes.

Hurricane Melissa’s story is still unfolding, but its message is already clear: resilience planning can’t wait for recovery.

Speak to a Climate Expert

Learn how forward-looking climate analytics from Jupiter Intelligence help organizations anticipate and prepare for the world’s escalating climate extremes. Contact us here.

References

- “Hurricane Melissa (2025) and Climate Change”. Climate Central. Updated 2025-10-28.

- Gilford, D.M., J. Giguere, and A.J. Pershing (2024): Human-caused ocean warming has intensified recent hurricanes. Environ. Res. Lett.: Climate, 3, 045019.

- Guzman, O., and H. Jiang (2021): Global increase in tropical cyclone rain rate. Nature Communications, 12, 5344.

- van Oldenbourgh, G., and coauthors (2019): Rapid attribution of the extreme rainfall in Texas from Tropical Storm Imelda. World Weather Attribution.

- Fulton, A., M. Singh, R. Luscombe, T. Ambrose, and Y. Lowe, 2025-10-28: “Jamaica braces as storm approaches”. The Guardian. Updated 2025-10-28

- Livesay, B., and O. O’Connell, ed. 2025-10-28: “Hurricane Melissa hits Jamaica with violent winds as authorities warn of ‘catastrophic’ flooding”. British Broadcasting Corporation. Updated 2025-10-28.

- Fernández, A., A. Rodríguez, and J. Myers, Jr, 2025-10-30: “Haiti, Jaaica and Cuba pick up the pieces after Melissa’s destruction”. Associated Press, updated 2025-10-30.

- National Hurricane Center page on Hurricane Melissa

- Clarke, B., and coauthors (2024): Climate change key driver of catastrophic impacts of Hurricane Helene that devastated both coastal and inland communities. Grantham Institute for Climate Change, Imperial College London.

- “Yet another hurricane wetter, windier and more destructive because of climate change”. 2024-10-11. World Weather Attribution.

- Uehling, J., and C. J. Shreck III (2024): Observed changes in extreme precipitation associated with U.S. tropical cyclones. J. Climate, 37

- Clarke, B., and coauthors (2024): Climate change increased Typhoon Gaemi’s wind speeds and rainfall, with devastating impacts across the western Pacific region. World Weather Attribution.

- Li, S. and Otto, F.E.L. (2022): The role of human-induced climate change in heavy rainfall events such as the one associated with Typhoon Hagibis. Climatic Change, 172: 7. doi.org/10.1007/s10584-022-03344-9.

- van Oldenbourgh, G., K. van der Wiel, A. Sebastian, R. Singh, J. Arrighi, F. Otto, K. Haustein, S. Li, G. Vecchi and H. Cullen (2017): Attribution of extreme rainfall from Hurricane Harvey, August 2017. Environ. Res. Lett., 12, 124009.

- Keelings, D., and J. J. Hernández Ayala (2019): Extreme Rainfall Associated With Hurricane Maria Over Puerto Rico and Its Connections to Climate Variability and Change. Geophys. Res. Lett., 46, 2964-2973.

- “Jamaica Hurricane Beryl Aftermath”. United Nations UNifeed. Updated 2024-09-11.

- Meenan, C. “Hurricane Beryl: How did Jamaica’s disaster risk financing stack up?” Centre for Disaster Protection.

.webp)