The 2026 Winter Olympics have begun, and the Alps highlight how warming temperatures are reducing the cold conditions that winter sports depend on. By 2050, many Alpine venues are projected to face increasing challenges, driving greater reliance on higher elevations and artificial snow. The future of the Winter Olympics in the Alps ultimately hinges on global emissions trajectories.

As we enter February 2026, the sporting world is turning to Italy to celebrate the Winter Olympics. However, amid athletic triumphs and dramatic mountain scenery, concerns continue to grow about the future of the Winter Games.

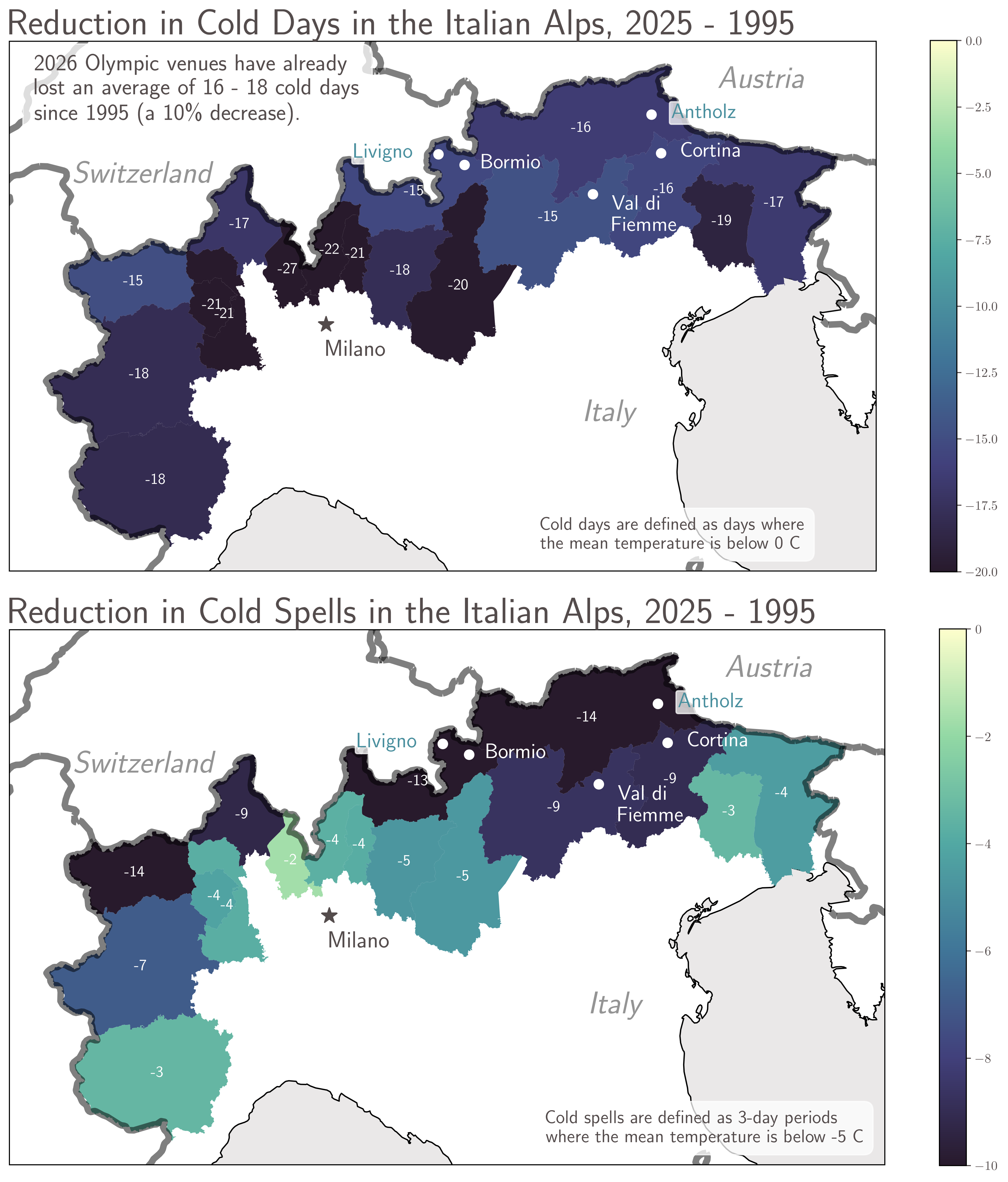

- The Italian Alps, home to the 2026 Winter Olympics, have seen an approximately 10% decrease in cold days and cold spells in the last 30 years;

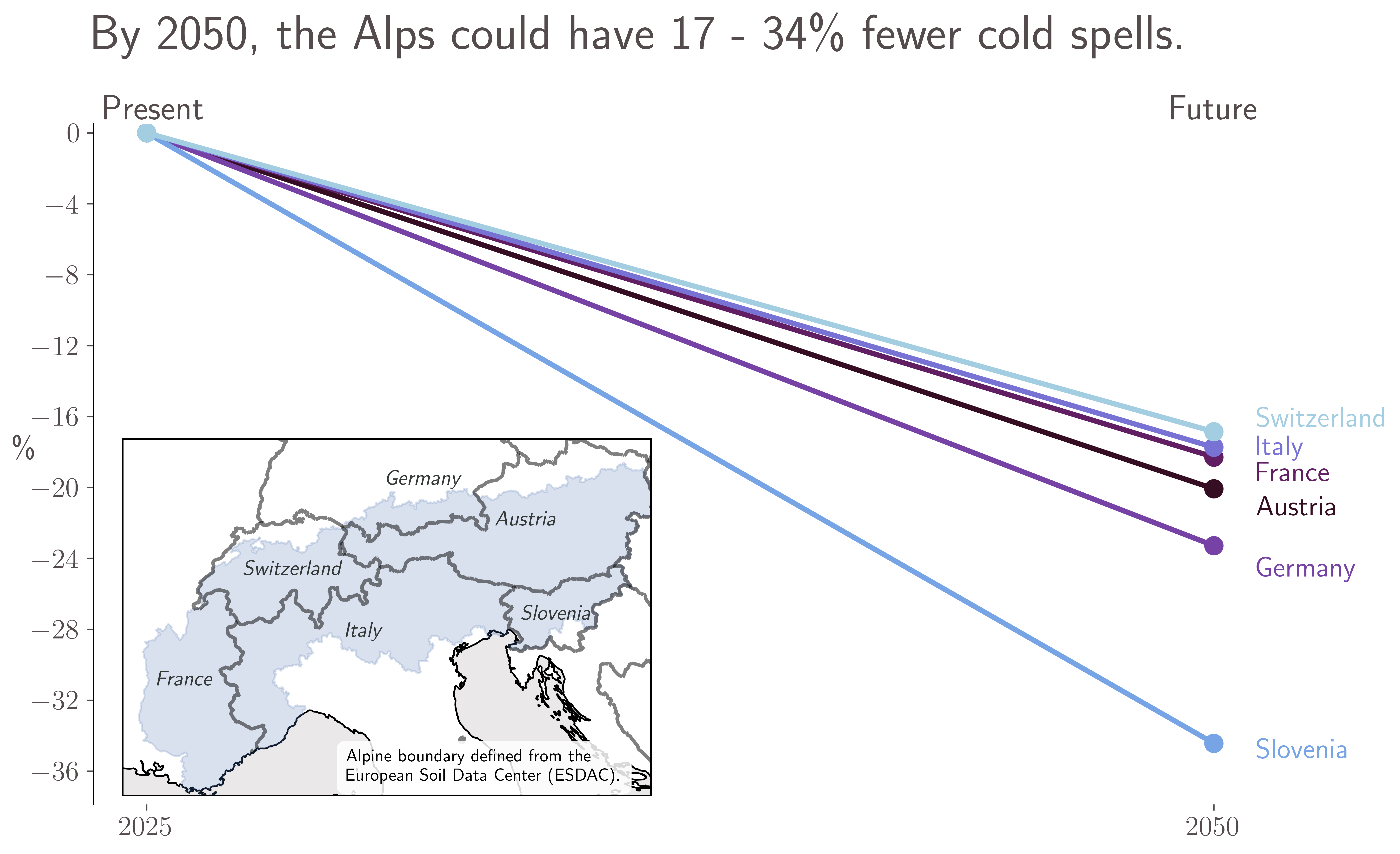

- The entire Alpine chain could see cold spells decrease a further 17-34% in the next 25 years;

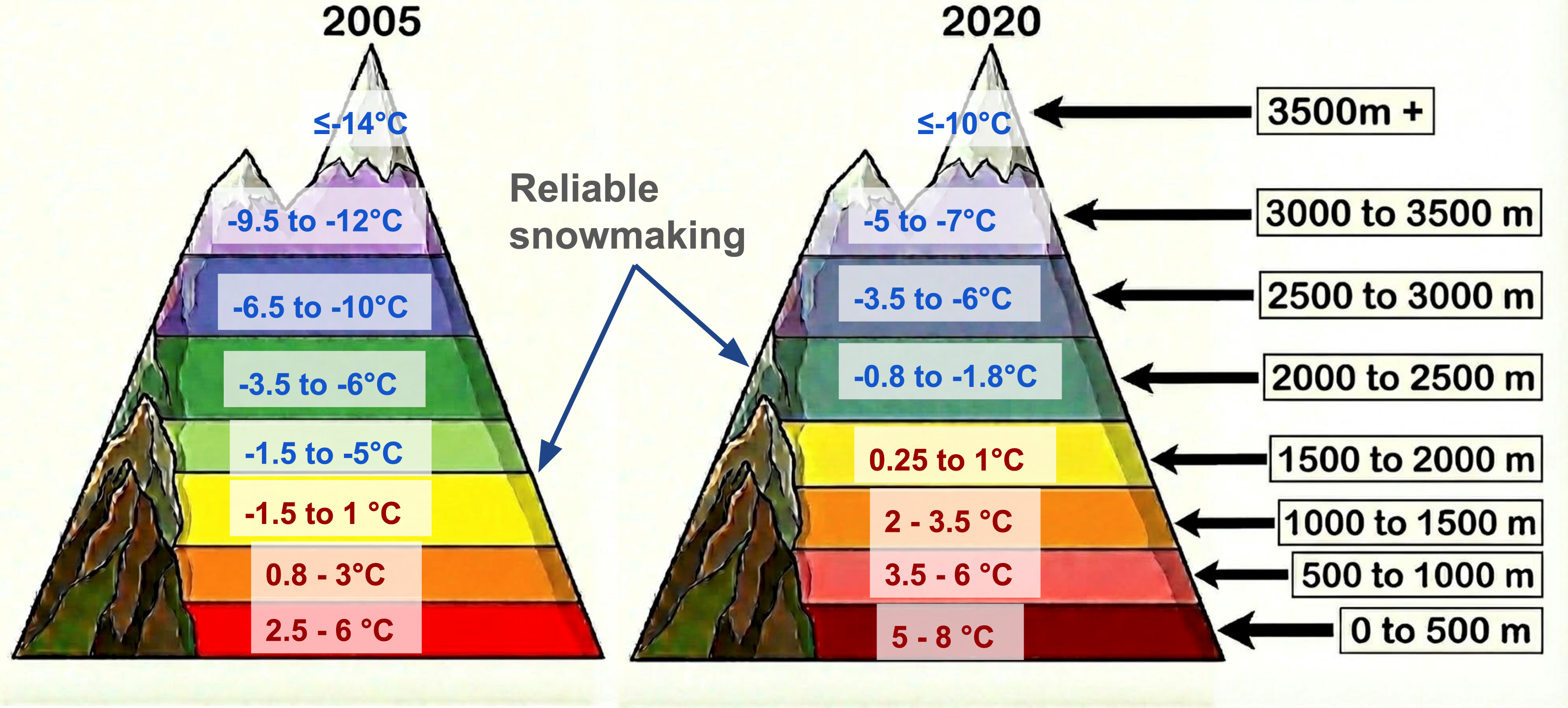

- Reliable skiing elevations have already relocated as much as 500 m (1640 ft) higher in elevation;

- An expansion of snowmaking and a shift to higher elevation locations can keep the Winter Olympics alive through the 2050s and beyond, though the number of reliable venues is decreasing;

- While the future of winter sports and winter tourism is uncertain, meeting the Paris Agreement emissions targets combined with investments in snowmaking can allow winter sports to survive into the next century.

A recent study of Winter Olympic and Paralympic venues suggests that 30% of potential hosts are already considered marginal or unreliable in the 2020s1.

As warming continues, which of the world’s iconic winter landscapes will still be cold and snowy enough to host the Olympics in 2050 and beyond?

The Winter Olympics in a Warming World

In 2022, the Beijing Olympics were held entirely on artificial snow, an Olympic first2. The 2022 Games required an estimated 49 million gallons of water to produce nearly 3 million cubic meters of artificial snow. In 2014, Sochi became the warmest city ever to host a Winter Olympics3, and in 2010, Vancouver famously trucked snow from higher elevations to prepare Olympic venues. This year, even the high-elevation venues of Cortina d’Ampezzo are preparing to make nearly 2.4 million cubic meters of snow for the Winter Olympics4. When Cortina last hosted the Games in 1950, competitions were held entirely on natural snow.

Yet the mountain regions that support winter sports have been losing snow rapidly in a warming climate. Around 78% of mountain areas worldwide, including the Alps, have lost snow since 2000, and some regions have experienced as many as 43 fewer days of snow cover over this period5.

The Alps and the Legacy of Winter Sports

The Winter Olympics have a long history in the Alps. The first Winter Olympics were held in 1924 in Chamonix, France. Nearly half of all Winter Olympic Games since then have taken place in the Alps, far more than in any other region. The Alps have hosted nearly 75% of alpine skiing world championships, almost 50% of freestyle skiing world championships, and about 30% of biathlon and cross-country skiing world championships.

Beyond elite competition, the Alps dominate global ski tourism. Roughly 79% of the world’s major ski resorts, defined as those with at least one million skier visits per season, are located in the Alps. Europe is the largest ski tourism market globally, and European ski tourism is heavily concentrated in the Alps, which account for 43% of annual global skier visits6. Winter tourism generates an estimated €69 billion ($81.5 billion) worldwide, with €33 billion ($39 billion) of that total generated in Europe7. Many smaller Alpine communities depend heavily on mountain tourism, particularly winter tourism. As temperatures rise and snowfall declines, the Alps face growing risks to both winter sports and the economies that depend on them.

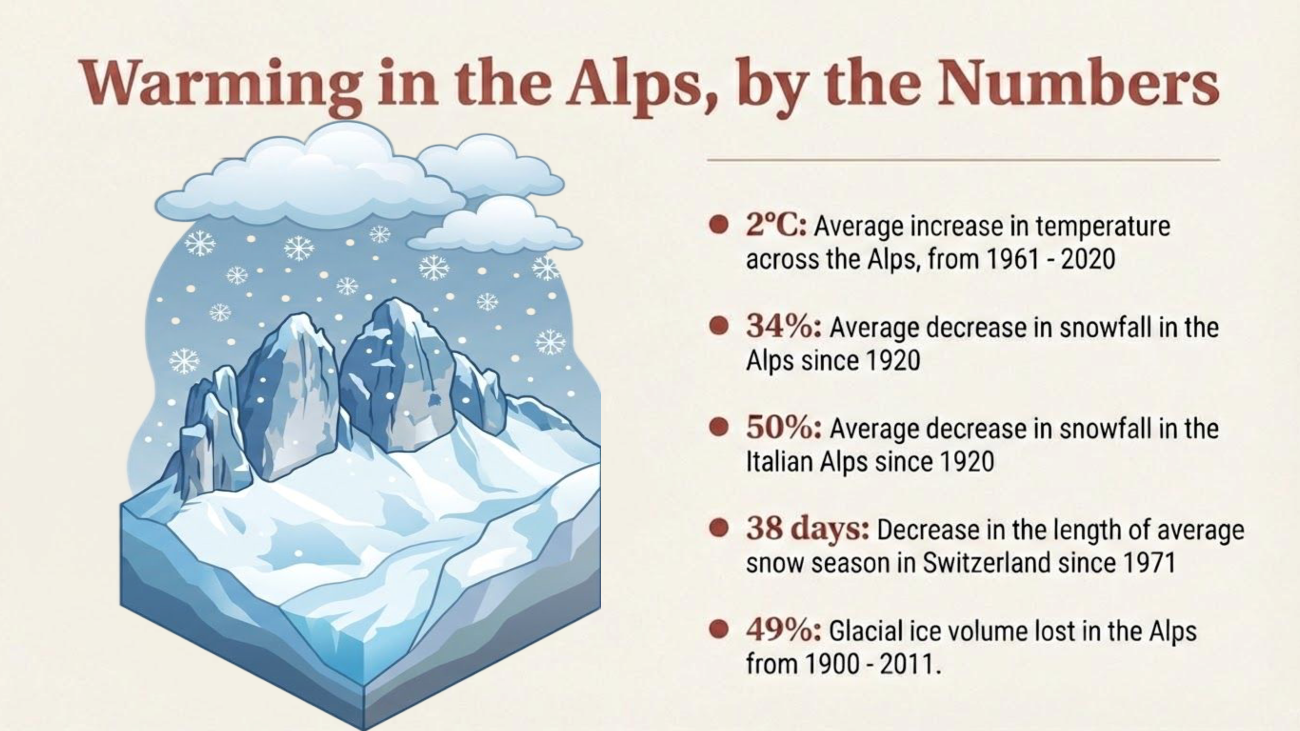

The Warming Alps

Over the past 50 years, the Alps have warmed substantially. Temperature increases have been observed across the entire region, with particularly rapid warming in the Southern and Western Alps, including much of Italy, France, and Slovenia. Alongside rising temperatures, Alpine snowpack has declined and the length of the snow season has shortened (see Figure 1). Snow losses are most pronounced below 2000m (6500 ft) in elevation, while higher elevations have been less affected8,9,10. At lower elevations, increases in precipitation increasingly fall as rain rather than snow, accelerating snow and ice melt8,9,10. Alpine glaciers have melted rapidly throughout the 20th and 21st centuries9, with warming accelerating since the 1990s.

Since 1992, only two Winter Olympic Games have been held in the Alps, Albertville, France in 1992, and Torino, Italy in 2006. Even over this relatively short period, warming has been substantial. In Torino, nearly every year since 2006 has been at least 0.5°C (0.9°F) warmer than the 1961–2010 average, while in France, seven of the last ten years have been more than 1°C (1.8°F) warmer than average11.

How Much Has Italy Warmed in Recent Years?

Since Italy last hosted the Winter Olympics in 2006, the Italian Alps have warmed substantially in all seasons. For January and February, Jupiter’s ClimateScore Global platform estimates that temperatures in 2025 were, on average, 2°C (3.6°F) warmer than a baseline period centered on 1995 (1984–2004). Across the Italian Alps, there were an estimated 15 to 27 fewer cold days in 2025 than during the baseline period. For cities hosting 2026 Olympic venues, an average of 13 to 16 cold days have been lost, while Torino, host of the 2006 Games, has experienced an average loss of 18 cold days.

Cold spells, defined as three-day periods with average temperatures below −5°C (23°F), have also declined rapidly. The 2026 Olympic venues have lost an estimated 9 to 14 cold spell days since the baseline period. These sustained cold conditions are critical for snowmaking, and their absence can make both snow production and snow preservation increasingly difficult.

Looking Ahead: Can the Alps Host the 2050 Winter Olympics?

Looking ahead to 2050, ClimateScore Global estimates that cold spells could decrease by 17–34% across the Alps, with declines of up to 66% under the high-emissions ssp5-8.5 scenario. Slovenia appears the most vulnerable, while Switzerland is the most reliable. Cold days are projected to decrease by an additional 5–10%, with reductions of up to 17% possible under high-emissions scenarios. Average January and February temperatures across the Alps are expected to increase by another 1°C (0.9°F) over the next 25 years.

By 2050, average February temperatures across the Alps could approach 1°C (34°F). At this threshold, roughly 50% of natural precipitation may fall as rain rather than snow, further accelerating snowmelt and complicating snowmaking12. The Paralympics, held in March, are even more exposed, with average March temperatures across the Alps potentially reaching 5°C (41°F) by mid-century.

Snow science research suggests that for every 1°C (1.8°F) increase in temperature, the elevation at which skiing is considered reliable rises by at least 150m (500 ft)13. A 3°C (5.4°F) increase over recent decades could therefore correspond to a 500m (1600 ft) upward shift in reliable snow conditions. In Italy, reliable skiing elevations could rise to 1800m (5900 ft), potentially leaving only about half of currently operating resorts viable14. By 2100, Alpine locations below 1200m (3900 ft) could become virtually snow-free, with winter seasons ending up to three months earlier in some areas13,15.

Is Higher Elevation the Solution?

While Alpine locations below 1500m (5000 ft) face the greatest risk of losing snow cover, higher elevations present a more complex picture. At elevations above 3000m (9800 ft), warming could initially lead to increased snowfall, since optimal temperatures for heavy snow range from 0 to −9°C (15 - 32°F). Locations that are currently much colder than this range may temporarily benefit as temperatures rise. However, by the end of the 21st century, even the highest elevations are expected to experience snowfall declines unless emissions are significantly reduced16.

Winter Sports in a Future with Less Snow

Snowmaking offers a partial buffer against declining natural snowfall, at least in the near term. As of 2022, 39% of ski slopes in France used artificial snow17. In Austria and Italy, over 70% of slopes rely on snowmaking18. With continued investment, snowmaking could halve the number of European ski resorts projected to be at very high risk under warming scenarios19.

However, artificial snow comes with substantial costs. A survey of Austrian ski areas found that during the 2023–2024 season, snowmaking consumed 43.8 million cubic meters of water and 281 GWh of electricity (5.3 kWh per skier visit), corresponding to an estimated 54 grams of CO₂ emitted per visit20. For the Milan–Cortina Olympics, Italy constructed multiple reservoirs to support snowmaking, including a 53 million gallon basin at Livigno and a 23 million gallon basin at Bormio4. As temperatures rise, both water and energy demands for snowmaking increase, with water requirements potentially underestimated by as much as 35%21.

Snowmaking infrastructure also requires substantial capital investment. Austria spent an estimated €800 million ($945 million) on snowmaking between 1994–2004, and a single Italian resort reportedly spent €5 million ($5.9 million) during the historically poor 2022–2023 winter season18.

Larger, higher-elevation resorts in the Alps may be able to survive by increasing their reliance on snowmaking. But 30% of ski resorts in the Alps are located at altitudes of 1300m (4300 ft) or lower – the altitudes most at risk for lack of reliable snow coverage. And snowmaking may not be enough for these low-elevation resorts, because as temperatures warm, snowmaking hours (which require temperatures below 0°C (32°F), and often even colder in the humid Alps decrease8. In Austria, for example, the number of snowmaking hours has decreased by an estimated 26% from 1961 - 2020, with much of this loss coming at lower-elevation resorts18. As recently as 20 years ago, seasonally averaged wintertime temperatures for Alpine locations between 1000 - 1500m (3200 - 5000 ft) hovered around 0°C, but by 2020, seasonally averaged wintertime temperatures have increased to 2 - 3°C (35 - 37°F)– well above viable snowmaking temperatures23.

Adaptation Efforts Have Made Progress

The quickest and easiest solution is to move up in elevation. For competitions such as the Olympics or skiing World Cups, this may mean adjusting competition rules. For cross-country skiing, the maximum elevation of race courses was recently raised to 2000m (6500 ft), from a previous maximum of 1800m (5900 ft)24. For tourists, this could mean fewer recreation opportunities, as smaller and lower-elevation ski areas disappear.

And while investment in snowmaking is common for alpine skiing facilities, other winter sports like biathlon and cross-country skiing will need to increase their investment in snowmaking and snow preservation techniques25,26. Furthermore, some snowsports areas have met the energy and water demands of snowmaking with green energy solutions. Resorts have greatly increased energy efficiency. In Vermont, ski resorts have saved more than 1 billion kilowatt hours of electricity from 2000 to 202227, while resorts such as Laax in Switzerland and Zell am See in Austria use renewable energy to power ski lifts, water pumps, and snow cannons28. But even with gains in efficiency and increased reliance on renewable energy, expanding the use of artificial snow depletes resources and increases the carbon emissions associated with winter sports.

Beyond Winter Sports

Winter sports bring in billions of Euros in revenue and employ thousands in the Alps. However, the mountains matter beyond winter tourism. Alpine glaciers and snowfields feed many major European rivers, including the Rhône, Rhine, Po, and several tributaries of the Danube. Warming temperatures, melting glaciers, and an increase in rain at the expense of snow can increase the probability of wintertime floods, and raise the risk of spring floods29,15. Less snow in the winter means less snowmelt to feed rivers in the spring and summer, meaning greater risks of water shortages19, and summer and fall droughts29. One study indicates that with enough glacier melt, the Rhône could dry up partially in some years29. Runoff from glacier and snowmelt also affects hydropower generation–crucial for nations like Switzerland and Austria, where over half of all power generated comes from hydropower19,30.

Hope for the Future: Emissions Reductions Can Save the Snow

The prospect of a warming world may feel bleak to winter sports lovers. However, it’s not all bad news. Much of the damage can in fact be mitigated if the Paris Agreement goals (keeping warming to 2°C of pre-industrial levels) are met. If warming is limited to 2°C (3.6°F), an expansion of snowmaking across ski resorts can reduce the impacts of warmer temperatures17. A recent study shows that if Paris Agreement goals are met, 52 of the 93 locations that could conceivably host the Winter Olympics would still be climate reliable in the 2050s, while 46 of these 93 locations would remain climate reliable in the 2080s1. Europe, which has hosted the most Winter Olympics, sees the largest decrease in reliable locations31. Continual improvement in snowmaking and snow preservation technology, along with investment in renewable energy and water recycling for snowmaking can increase the sustainability of artificial snow in winter sports.

However, the time to act is now. Up to the present, snow loss trends in the Alps have been as bad as predicted if not worse, and the United Nations Development Programme estimates that the world is currently on track for 3°C (5.4°F) of warming. While ski resorts can survive and adapt to a 2°C warmer world, the picture is much grimmer for 3°C of warming or more. In the U.S., ski resorts could lose up to $1.3 billion per year if Paris Agreement emissions targets are not met34. In the Alps, snowmaking expansion in France would essentially be neutralized by temperatures of 3°C17. In ski-crazy Austria, 63% of the population now does not ski – up from 42% non-skiers in the 1980s18. Leaders in recreation and winter tourism must seize this opportunity to advocate for sustainable development and lower emissions going forward, or else they risk enormous revenue loss now and in the future.

References

- Steiger, R., and D. Scott, 2025: Climate change and the climate reliability of hosts in the second century of the Winter Olympic Games. Current Iss. in Tourism, 28, 3661-2674. doi:10.1080/13683500.2024.2403133.

- University of Pittsburgh. (2022). Winter Olympics and climate change. Pitt Global Hub. Retrieved January 10, 2026.

- Wagstaffe, J., February 21, 2014: Sochi Olympics wins gold for warmest temperatures. CBC News. Retrieved January 10, 2026.

- McDermott, J., and P. Graham, January 23, 2026: Italian expert's manufactured snow will play big role at the Milan Cortina Games. AP News. Retrieved 5 February 2026.

- Notarnicola, C., 2020: Hotspots of snow cover changes in global mountain regions over 2000–2018. Remote Sensing Environment, 243, 111781. doi:10.1016/j.rse.2020.111781.

- Vanat, L., 2022: 2022 International Report on Snow & Mountain Tourism. Retrieved January 22, 2026.

- Turuban, P., December 18, 2020: The importance of ‘white gold’ to the Alpine economy. SwissInfo. Retrieved January 10, 2026.

- Bozzoli, M., and coauthors, 2024: Long‐term snowfall trends and variability in the Alps. Int. J. Climatology, 44, 4571-4591. doi:10.1002/joc.8597.

- Beniston, M., and coauthors, 2018: The European mountain cryosphere: a review of its current state, trends, and future challenges. The Cryosphere, 12, 759 - 794. doi:10.5194/tc-12-759-2018.

- Bongiovanni, G. (2025). Temperature and precipitation trends in the Extended European Alpine Region over 1961 -2020. Doctoral dissertation. Scuola Universitaria Superiore Pavia.

- Hawkins, E. “Show Your Stripes”. Institute for Environmental Analytics. Retrieved 4 February 2026.

- Kienzle, S., 2008 A new temperature based method to separate rain and snow. Hydrological Processes, 22, 5067 - 5085. doi:10.1002/hyp.7131.

- Gilaberte-Búrdalo, M., F. López-Martín, M.R. Pino-Otín, and J.I. López-Moreno, 2014: Impacts of climate change on ski industry. Environ. Sci. and Policy, 44, 51 - 61. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2014.07.003.

- Marty, C., S. Schlögl, M. Bavay, and M. Lehning, 2017: How much can we save? Impact of different emission scenarios on future snow cover in the Alps. The Cryosphere, 11, 517 - 529. doi:10.5194/tc-11-517-2017.

- Klein, G., Y. Vitasse, C. Rixen, C. Marty, and M. Rebetez, 2016: Shorter snow cover duration since 1970 in the Swiss Alps due to earlier snowmelt more than to later snow onset. Climatic Change, 139, 637 - 649. doi:10.1007/s10584-016-1806-y.

- Frei, P., S. Kotlarski, M.A. Liniger, and C. Schär, 2018: Future snowfall in the Alps: projections based on the EURO-CORDEX regional climate models. The Cryosphere, 12, 1 - 24. doi:10.5194/tc-12-1-2018.

- Spandre, P., and coauthors, 2019: Climate controls on snow reliability in French Alps ski resorts. Nature Scientific Reports, 9, 8043. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-44068-8.

- Andriot, P., M. Laurent, and M.-L. Ghib, January 2024. “Climate Change in Mountain Areas: Meeting the Challenge of Adapting Water Management and Tourism.” Agence Nationale de la Cohésion des Territoires, République Française. Retrieved January 30, 2026.

- François, H., and coauthors, 2023: Climate change exacerbates snow-water-energy challenges for European ski tourism. Nature Climate Change, 13, 935 - 942. doi:10.1038/s41558-023-01759-5.

- Aigner, G., R. Steiger, and M. Mayer, 2024: Snowmaking in Austria: Energy consumption, water turnover, CO2 emissions. Current Issues in Sport Science (CISS), 9, 028. doi:10.36950/2024.4ciss028.

- Steiger, R., N. Knowles, K. Pöll, and M. Rutty, 2024: Impacts of climate change on mountain tourism: a review. J. Sustainable Tourism, 32, 1984-2017. doi:10.1080/09669582.2022.2112204.

- Damm, A., J. Köberl, and F. Prettenthaler, 2014: Does artificial snow production pay under future climate conditions? – A case study for a vulnerable ski area in Austria. Tourism Management, 43, 8 - 21. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2014.01.009.

- Bongiovanni, G., Matiu, M., Crespi, A., Napoli, A., Majone, B., & Zardi, D. (2024). EEAR-Clim: A high density observational dataset of daily precipitation and air temperature for the Extended European Alpine Region [Data set]. Zenodo. doi:10.5281/zenodo.14218564.

- Roth, K., May 15, 2024: Higher Elevations, More Skiathlons—World Cup Schedule and Rule Changes Announced. Faster Skier. Retrieved 2 February 2026.

- Landauer, M., U. Pröbstl, and W. Haider, 2012: Managing cross-country skiing destinations under the conditions of climate change – Scenarios for destinations in Austria and Finland. Tourism Management, 33, 741 - 751. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2011.08.007.

- Wolfsperger, F.: Snowfarming – preserving snow over the summer. WSL Institute for Snow and Avalanche Research SLF. Retrieved February 2, 2026.

- Root, T., February 23, 2024: Greener snowmaking is helping ski resorts tackle climate change. The Guardian. Retrieved February 2, 2026.

- Maczko, E., February 3, 2026: Inside 5 Sustainability-Focused European Ski Resorts. Forbes. Retrieved February 3, 2026.

- Beniston, M., 2012: Impacts of climatic change on water and associated economic activities in the Swiss Alps. J. Hydrology, 412, 291-296. doi:10.1016/j.jhydrol.2010.06.046.

- Euractiv, Sept. 30, 2024: Climate change challenges hydropower-dependent Austria. Euractiv, accessed February 2, 2026.

- Scott, D., Steiger, R., & Orr, M., 2026: Advancing climate change resilience of the Winter Olympic-Paralympic Games. Current Iss. in Tourism, early access. doi:10.1080/13683500.2026.2617880.

- Schilling, S., and coauthors, 2026: Ski Areas and Snow Reliability Decline in the European Alps Under Increasing Global Warming—A Remote Sensing Perspective. Remote Sensing, 18, doi:10.3390/rs18030491.

- United Nations Environment Programme, November 4, 2025: Emissions Gap Report 2025. United Nations Environment Programme. Retrieved February 2, 2026.

- Scott, D., and R. Steiger, 2023: How climate change is damaging the US ski industry. Current Iss. in Tourism, 27. doi:10.1080/13683500.2024.2314700.

- Matiu, M., and coauthors, 2021: Observed snow depth trends in the European Alps: 1971 to 2019. The Cryosphere, 15, 1343-1382. doi:10.5194/tc-15-1343-2021.

- Panagos, P., Van Liedekerke, M., Borrelli, P., Köninger, J., Ballabio, C., Orgiazzi, A., Lugato, E., Liakos, L., Hervas, J., Jones, A. Montanarella, L., 2022: European Soil Data Centre 2.0: Soil data and knowledge in support of the EU policies. European Journal of Soil Science, 73(6), e13315. doi:10.1111/ejss.13315.

.webp)