“Adapt or perish, now as ever, is nature’s inexorable imperative.”

H. G. Wells, the author and futurist, wrote that famous phrase in 1945. His words are more prophetic than ever today for an insurance industry struggling with the burgeoning risk to people, property, communities, and economies caused by climate change.

“Natural disasters” caused $210 billion (U.S.) in damages globally in 2020, according to Munich Re’s January report, a 26.5 percent increase from 2019’s $166B. Insured losses rose 44% to $82B. In the United States, losses from extreme weather events—floods, wind, wildfires, and hail—hit $95B, almost doubling the toll exacted by 2019, while insured loss in 2020 climbed 158% to $67B. Climate-change-driven disasters punished broad swaths of the country in 2020: the Midwest joined the hurricane-prone Gulf Coast and the wildfire-vulnerable West among the ranks of the devastated, reporting $7 billion in losses from one August derecho alone.

Are insurers truly aware of the systemic threats posed by physical climate risk? Are they “prepared to prepare” for it?

Insurers appear to be incorporating physical climate risk into their business at different paces; reinsurers and brokers have taken the lead, according to Kia Javanmardian, leader of McKinsey’s North American P&C Practice, but primary line carriers diverge in their thinking. “There’s a bit of difference in opinion on ‘Can I just price this in over time?’ versus ‘Do I need to make a more proactive stance?’” he noted in the January 2021 podcast How Insurance Can Combat Climate Change.

A reluctance to price physical risk into the market may be due to a traditional belief that it is harder to model than transitional risk, as Jupiter’s Meghan Purdy wrote in January. Yet as she noted in October 2020, physical climate risk may be challenging to assess, but it now can be quantified and predicted.

The combination of natural and man-made pressures and the advancement of climate modeling and analytics mandate that every insurance firm get on a path toward the integration of physical climate risk into their core operations, or risk being left in the dust.

Three Stages of Physical Climate Risk Adoption

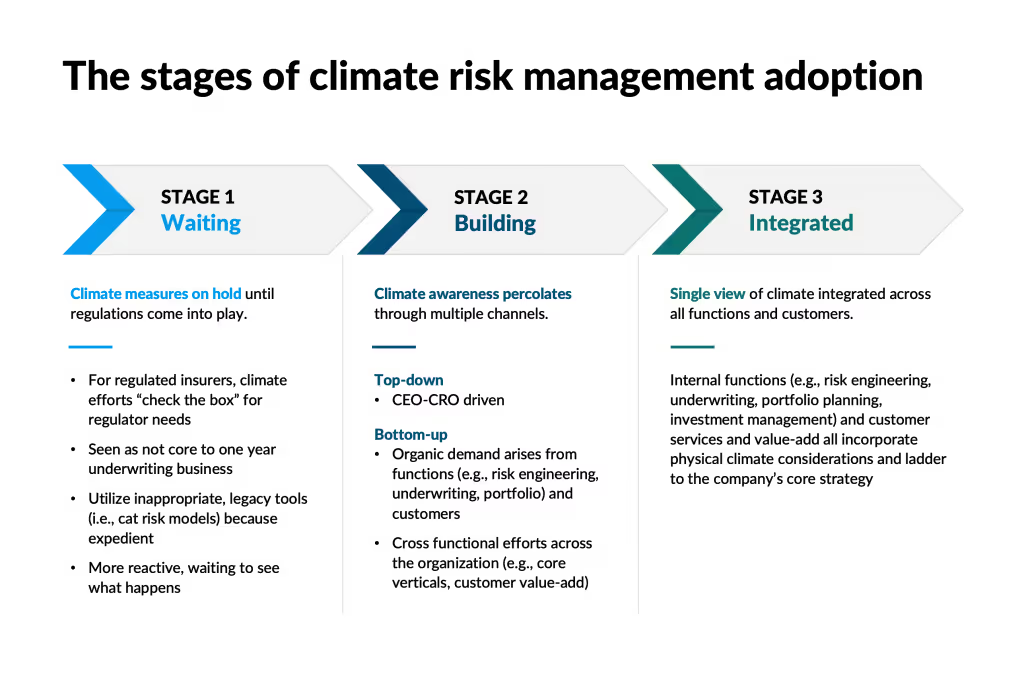

An adoption maturity model (Figure 1 below) is coming into focus, based on Jupiter’s interactions with a broad cross-section of insurers. Firms tend to fall into three categories—Waiting, Building, and Integrating—and while most insurers today belong to the Waiting classification, the bulk of them will be forced to become Integrators well before 2030.

Stage 1: Waiting

The Waiting class are largely holding fire until climate-oriented regulation impacts their geography. Even some firms in regulated jurisdictions—for example, in the U.K., where the Prudential Regulatory Authority has developed stress testing and significant guidelines—opt for an approach that is little more than “check the box.”

Some use legacy solutions, like catastrophe models, that were never designed for such a purpose. Many of these tools do not incorporate climate models; instead, they base their results on tweaked historical data, which is of little use in a time when the climate is changing.

Cat modeling also tends to focus on acute costs in “valuable,” high-premium regions, without taking into account geographies in the developing world, which are most affected by climate change. They may also ignore chronic issues such as nuisance flooding, air conditioning costs, weaker crop yields, and lower worker productivity. These factors may not lead to an insurance claim, but they can decisively impact an investment portfolio.

“We can’t, as an industry, continue to just collect more and more money, and rebuild and rebuild and rebuild in the same way. We’ve got to place an emphasis on preventing and reducing loss.”

—Donald L. Griffin, vice president

American Property Casualty Insurance Association

Stage 2: Building

Builders are actively developing internal capabilities to incorporate climate risk into their operations. This practice is emerging in two ways that often work in tandem:

In a Bottom-Up initiative, climate awareness percolates up through multiple channels:

- Enterprise risk, via the Chief Risk Officer. Some CROs view regulatory mandates as an opportunity to examine changing risks and consider long-term implications on policy portfolios, with proactive steering of exposures and aggregates.

- Investment management. Real asset (commercial real estate and infrastructure) and financial asset (equities and bonds) portfolios are analyzed for impacts from physical climate risk. These actions, according to Oliver Wyman in Addressing Climate Change (2020), are driven by stakeholder, activist, and media scrutiny; frameworks like TCFD; and the need to sustain corporate reputation and brand equity through rigorous, comprehensive climate risk disclosures.

- Risk engineering. Insurers are fundamental to risk engineering because they offer incentives via lower premiums for clients who build for the long term. A push-pull effect is occurring:

- The push: Insurers need to understand the future climate risks that face a client’s assets and ensure they are building resiliently. “We can’t, as an industry, continue to just collect more and more money, and rebuild and rebuild and rebuild in the same way,” says Donald L. Griffin, vice president of the American Property Casualty Insurance Association. “We’ve got to place an emphasis on preventing and reducing loss.”

- The pull: On the other hand, customers are asking for guidance from their insurers. Firms wanting to retain “trusted advisor” status are responding with new resilience/adaptation services and value-added solutions.

- Underwriting. With insurers seeing more “surprise, chaotic” losses, they need more than historical data and catastrophe models: they need to understand how much the climate is changing. Despite the one-year nature of policy writing, they must consider longer-term risks being entrenched in a market that may radically deteriorate five or ten years into the future. On a positive note, related to product development, the UN spies a “major opportunity going forward … to deepen the connection of scenario-based climate risk assessment frameworks to insurance products, including policy terms and conditions.”

A Top-Down initiative, led by the insurer’s senior executive management (especially the CEO) actively builds a connective tissue—creating cross functional councils and embedding key accelerating functions throughout the organization.

Organizations that have the right balance of bottom-up and top-down momentum will have a smoother, swifter path to integration.

“Those that hesitate to respond to climate-related challenges and opportunities will soon find themselves out-of-step with customers, employees, regulators, policymakers, and peer financial institutions—and, just as importantly, with the very essence of why they exist: to meet long-term promises that no other institutions can.”

—“Addressing Climate Change”

Oliver Wyman

Stage 3: Integrated

The need for a holistic view of both current and future physical climate risk demands a single, enterprise-wide view of climate impacts that is integrated across insurance firms’ internal functions and global client portfolios.

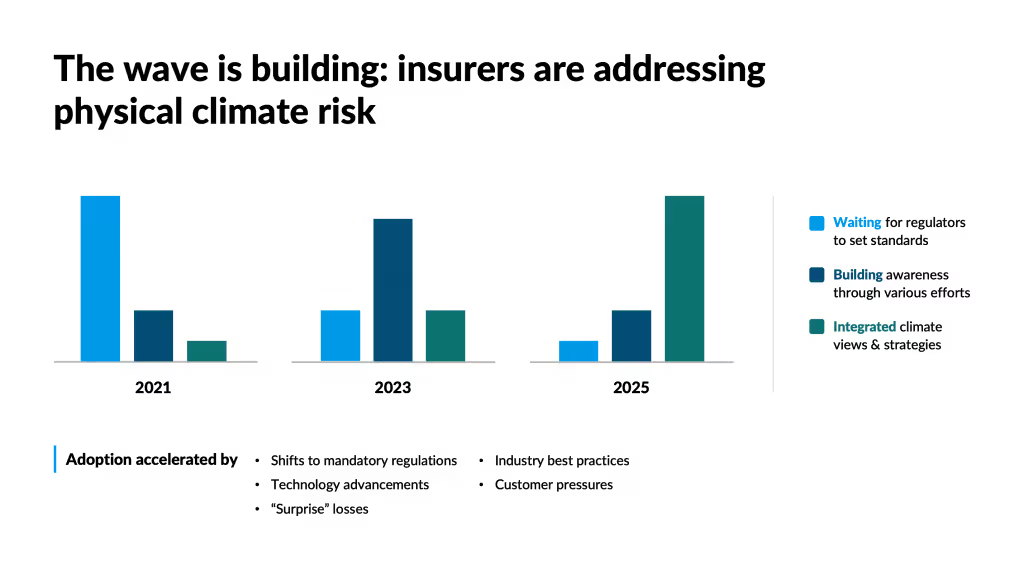

While very few major insurers have made this leap as of early 2021, an accelerated adoption scenario (Figure 2), driven by mandatory climate risk disclosure regulations, continued “surprise” losses, customer and stakeholder pressures, industry best practices and competitive forces, and technology advancement will change the landscape within this decade. Emerging best practices, led by the banking sector, and the elevation of risk experts to board-level positions and the strengthening of the risk management function signal a more aggressive adoption approach.

“Waiters” must become “Builders” with a minimum of delay. Urged the Boston Consulting Group in August 2020: “Insurance brokers can…adjust their risk solution offerings to reflect challenges created by climate change.”

One such Builder is Liberty Mutual. “We see the impact of climate change firsthand,” said Brendan Smyth, its senior vice president, Global Risk Solutions. Liberty Mutual is using best-in-science physical risk analytics to better determine “how to successfully identify, mitigate, and manage climate-related risks with new insurance products and services.”

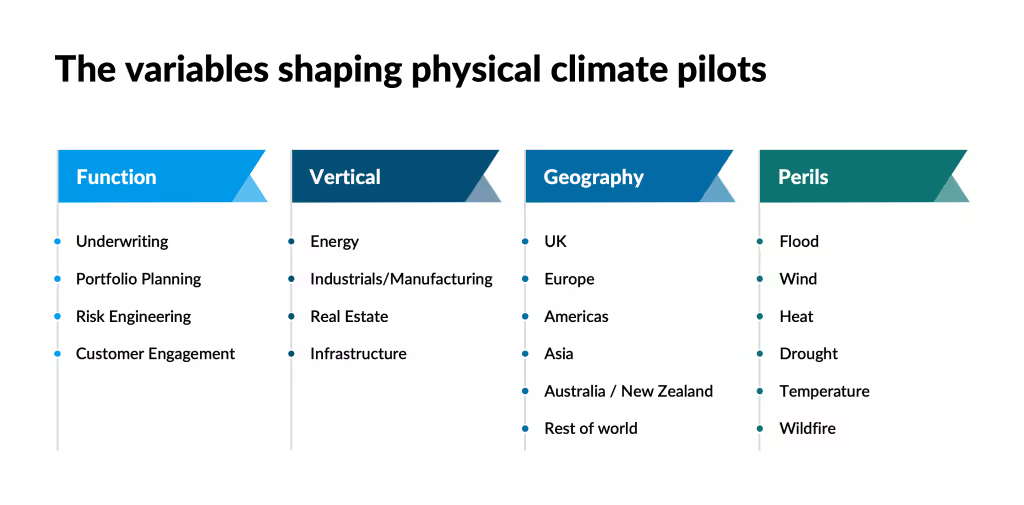

As they become Integrators, Builders must think strategically about how to link pilot efforts together to create connectivity/integration within their organization (Figure 3), across business functions, client verticals, relevant geographies, and climate-related perils, or some other combination.

Steps that Insurers Can Take Now

Those teams can have best-in-science physical risk data at their fingertips. The advancement of Global Climate Models (such as CMIP6), and techniques such as dynamical downscaling that have been enabled by technology breakthroughs like cloud computing, machine learning, and AI, have given insurers tools—such as Jupiter’s—to probabilistically predict the impacts of climate change on global portfolios and individual assets.

BCG also noted that insurers can “amplify the impact of their climate actions” by joining “prominent coalitions…in investments (such as the UN’s Principles for Responsible Investment), insurance (the Insurance Development Forum, the Geneva Association, and PSI), and in the general area of climate action (the UN Global Compact).”

“[Physical risk]…is, I think, under-appreciated, how near-term it is, how non-linear some of the impacts are,” said the head of McKinsey’s Sustainability Practice, Dickon Penner, in January 2021. “Also, as we know, the impacts will be systemic and potentially highly regressive.”

With senior leadership, including CEOs, onboard and ready to roll up their sleeves, insurers can prepare for the onslaught of climate change. “Insurers have started moving in the right directions,” Antonio Grimaldi, a partner in McKinsey’s London office, said in January, “but I think much more can and should be done.”

As Oliver Wyman counseled life insurers in Addressing Climate Change: “Those that hesitate to respond to climate-related challenges and opportunities will soon find themselves out-of-step with customers, employees, regulators, policymakers, and peer financial institutions—and, just as importantly, with the very essence of why they exist: to meet long-term promises that no other institutions can.”

.webp)